I interviewed Clyde Stubblefield, who was one of James Brown’s key drummers from 1965 to 1971. He played on “Cold Sweat,” which needs no introduction, and “Funky Drummer,” perhaps the most sampled beat ever.

It was an honor to talk to Clyde. It was also an honor to talk to Ahmir Thompson, a.k.a. Questlove of the Roots. We all know how great a drummer Ahmir is, and most probably also know that he’s a scholar and a very thoughtful guy about music. But I was still surprised by how insightful and eloquent he could be just speaking off the top of his head. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been. But his interview was too good to leave at two short quotes.

So here’s our full conversation, minus some shop talk at the end when he referred me to Alan Leeds, who was Brown’s tour director at the time and is a primary historian on all things James Brown. (With Quest’s help I did reach Alan, who was awesome. He has one of the more incredible behind-the-scenes careers in music: after Brown, he worked as the tour manager for Funkadelic, then for Prince for most of the 1980s, and later for D’Angelo.)

One thing that did surprise me about Quest, though, was that he talked a little like Mr. Micawber.

Ahmir: In short, there have been faster, and there have been stronger, but Clyde Stubblefield has a marksman’s left hand unlike any drummer in the 20th century. The thing that defines him, that sets him apart from other drummers, are his grace notes, which are sort of like the condiments of what spices up the main focus. The main focus of music is always the 2 and the 4, especially with the snare drum. And what lets you build your personality is how you dance around that 2 and the 4. The technical level of dynamics of his left hand, his ability to flam a 32nd note very silently, but a 16th note very loud and commanding. It takes a very, very specific marksman, in their Navy SEAL precision, to execute it perfectly. In short, it is he who defined funk music, more than anything.

Me: Was Clyde James Brown’s best drummer of all?, Better than Jabo, Bernard Purdie, etc.?

I’ve learned that to use good and bad, or to use best and worst, is not apropos. I believe that Clyde was the most effective drummer that James Brown has ever utilized. Jabo was his most powerful drummer, but Clyde was the most effective.

James Brown used all his musicians as percussion players; it’s just that the other nine musicians were melodic players. They basically played a loop. Very rarely would a James Brown song go to linear thoughts, where you didn’t know what was coming next. It’s a four-bar loop every time, very disciplined, very tight. Clyde’s whole gift is that he was able to incorporate everyone’s role in it. The main kick and main snare are kind of like the traffic cop, but the hi-hat could emulate what the guitar was doing. His snare work really emulated Jimmy Nolen, and a lot of their rhythms were very precise 16th and 32nd notes.

I felt as though Clyde was the most effective in completing the puzzle. His grace notes, his softest notes, defined a generation. It’s like the kind of ketchup you use, the things that surround the burger, as opposed to the burger itself.

Did Clyde have more influence as a drummer, on actual James Brown records, or as a sample?

More influence as a sample, hands down. Clyde’s influence is more unique than his actual work for James Brown.

It’s kind of weird, but I think his work with James Brown is too potent. As a DJ, I rarely play “Funky Drummer.” I rarely play “Soul Power.” But probably the record of choice, that has just enough sugar for the medicine to go down for most DJ’s, is the live version of “Give It Up or Turnit A Loose.” That’s a b-boy anthem, for most dancers. That song right there can be handled in a single dosage in a club. It’s like a jalapeño: you don’t want to just eat up the whole jalapeño, you want to cut it up and use it to spice your foods. And no, I won’t just use food metaphors here!

What about other popular samples, like the “Amen break”?

“Amen” and “Apache” were also very influential, and they had an influence in Europe, on jungle, drum ’n’ bass. But for the true experts of drum ’n’ bass, the “Soul Pride” break is hands down the go-to break. And that has really inspired a movement of great dance music: drum ’n’ bass, not to mention Baltimore house music. Baltimore house is still a subgenre; it might not be the next big thing that people predicted three or four years ago. But it’s still a phenomenon.

“Funky Drummer” has done miracles for hip-hop. It’s the traffic cop. The greatest hip-hop album of all time, “It Take a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” by Public Enemy — it’s all over that record. And that was intimidating to me. On Tuesday we’re doing “Fight the Power” with me and Clyde on drums, and Chuck D. That song is basically “Soul Pride” on steroids.

Does that mean that Clyde’s whole influence through the “Funky Drummer” sample distorts who he was as a musician? Since people weren’t really hearing the whole picture of who he was, just hearing a five-second break?

He’s like the ghost in the machine. When you talk about the most perfect beat, it’s not even that “Funky Drummer” wins in a technical aspect. But in an artistic aspect, it’s hands down the most perfect beat you can loop — it’s very lyrical, very melodic, very rhythmic. It’s perfect. It’s magical. Everyone I know as a producer, that’s gotten their start hip-hop production, they all have their story about the first time they heard “Funky Drummer.”

When I first heard “Funky Drummer,” I had James Brown’s “In the Jungle Groove” album. I gave it to my father as a Christmas gift. I knew he liked James Brown. I had that album for like four months. I don’t know why or how we let it sit for so long without investigating it. Maybe it’s because “Funky Drummer” was the only single during James Brown’s hit period, of roughly 1965 to 1975, when he had something like 70 top 10 hits, it was the only single that never reached the top 10.* Ironically, it was also one of Clyde’s last sessions with the James Brown Orchestra before Bootsy and his team came in.**

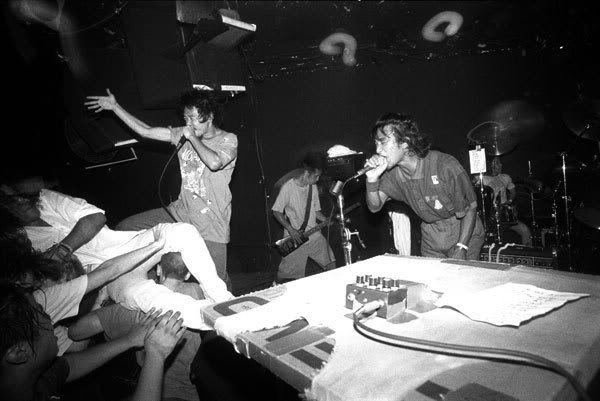

On Tuesday we are getting him to sit in with us. But any time I’ve seen Clyde footage of him playing somewhere, I’ve always been chagrined they have him on a new drum set that’s horribly tuned, so it sounds nothing like Clyde from the 1960s. So this time I am personally bringing out my 40-year-old Yamaha kit for him.

* Not quite, but you get the idea. Between 1965 and 1975, James Brown had 65 songs in the R&B top 40, and 44 of them reached the top 10. (“Funky Drummer” reached No. 20.) On the pop charts for the same period, Brown had 37 top 40 hits, 6 in the top 10.

** In March 1970, most of Brown’s band mutinied, demanding better treatment and pay. Brown fired them and put together an almost entirely new group, including the young Bootsy and Catfish Collins; that new band became known as the JB’s.

Clyde’s history is a little confusing at this point. According to Alan Leeds, Clyde was not present during the 1970 mutiny; he had left in December 1969, and he returned in June 1970 for a stay of about six months. (Note that Clyde played on “Get Up, Get Into It and Stay Involved,” recorded in November 1970.) Leeds says that Clyde next left again in late 1970: the band was going to Africa and Clyde had a problem with his paperwork. He returned for a short period in late 1971, and then left for good.