A wide-ranging and extremely well funded investigation by this blog has uncovered the astounding story behind one of the most beloved names in American entertainment.

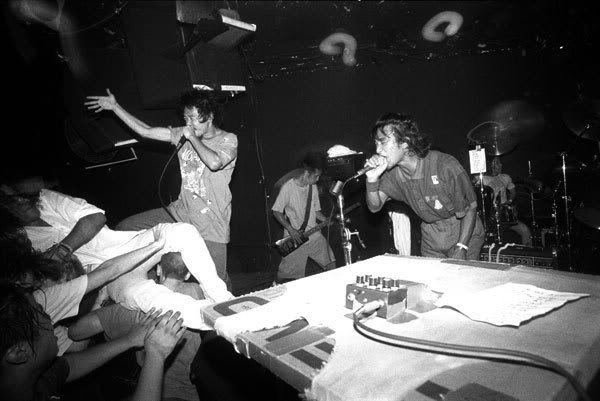

Many know and admire Frank Black as the leader of the Pixies and the singer of favorites like “Kicked in the Taco.” But according to documents unearthed at a flea market in Manhattan and corroborated by extensive research, the name had a prominent association long before it became the favored pseudonym of Charles Michael Kittredge Thompson IV.

In other words, there was a Frank Black who was Frank Black before Frank Black became Frank Black (after first being known as Black Francis)!

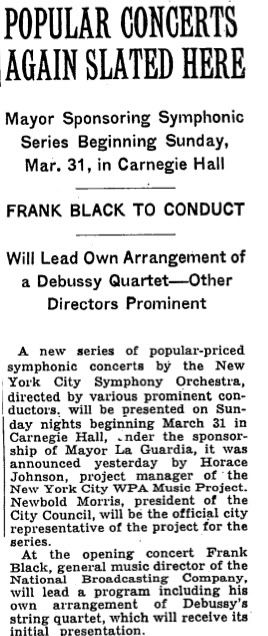

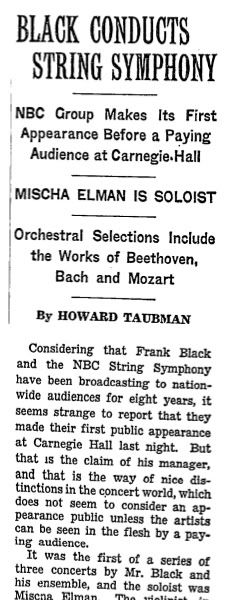

Decades before “you fuckin’ die,” back in the 1930s and ’40s, another Frank Black was known to radio listeners as the music director of the esteemed NBC Symphony Orchestra. Conducting classical music and lite fare, he was heard by millions each week. And in that emergent middlebrow era, when most high-culture posts in this country were filled by Europeans, the Philly-bred Black, with his slicked-back hair and tortoise-shell glasses, was an approachable, relatable American, not unlike Bernstein or Copland.

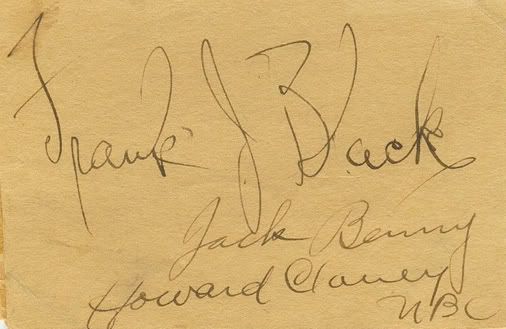

Dude had connections. Toscanini and Stokowski frequently borrowed the NBC orchestra, and when President Truman’s daughter, Margaret, attempted a singing career, Black conducted her Carnegie Hall debut on Dec. 20, 1949; her program included Christmas tunes and an aria from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. (Miss Truman’s parents were not in the audience, though Eleanor Roosevelt was.)

Charles Thompson, the Frank Black you saw on the Pixies reunion tour, did not respond to a request for comment.

Don’t Ya Rile ’Em!

This Frank Black — Frank Jeremiah Black — was born in Philadelphia on Nov. 28, 1894, to a prosperous Quaker dairyman. Dad “had every hope that his son would take over his work,” wrote David Ewen in his 1943 book Dictators of the Baton, “but Frank Black had a mind of his own.”

He enrolled at nearby Haverford College as a chemistry student, but soon found his way to music. Beginning a career that would straddle classical and pop tastes, Black studied in New York with Rafael Joseffy, a renowned Hungarian pianist and composer, but he paid the bills writing for vaudeville and doing other musical odd jobs, which vary according to biographer. Was he running his own player piano roll company or his own record company? Editing a magazine or editing scores for a Philadelphia music publisher?

Anyway, it was journeyman work until he made his way to Tin Pan Alley and Broadway at age 21. He arranged and directed musicals for the likes of Gershwin, Ziegfeld, Kern, and Rodgers & Hart, and by 1926 he had joined the Revelers, a popular vocal quartet, as pianist and arranger. Black’s arranging skillz in hits like “Ol’ Man River” and “Yankee Rose” helped the Revelers become the most imitated close-harmony group of their time.

He also quickly stepped out as a bandleader. Frank Black and His Orchestra were scoring hits on the Brunswick label as early as 1927, with “The Best Things in Life Are Free” and “The Varsity Drag,” the pre-Jitterbug collegiate dance number from the musical Good News:

You can pass many a class,

Whether you’re dumb or wise,

If you’ll all answer the call when your professor cries:

“Everybody down on the heels, up on the toes,

Stay after school and learn how it goes.

Everybody do the varsity drag!”

Go Frank Black go!

No Time for the Man Called Czar!

The success of the Revelers was Black’s ticket into the radio biz. At some point, according to Ewen, he was approached by NBC executives asking “if he would consider a radio post.”

Black, thinking of the deplorable lack of good music over the air, said he would; but his ambition in this direction was to organize a string symphony orchestra, and to conduct it as a regular radio feature in the best music of all time.

They went for it. And while it’s not clear whether “the best music of all time” was to include opening sets by Jonny Polonsky and Reid Paley, Philly Frank had scored big. In 1928 he became NBC’s music director, and thus a prominent figure in American cultural life. He churned out show after orchestral show throughout the 1930s and ’40s for a blur of sponsors: “The Magic Key Hour,” “Carnation Contented Hour,” “General Motors Symphony of the Air,” “The Bell Hour” and “Harvest of Stars” (sponsored by International Harvester), for which the publicity photos at the top and bottom of this post were taken circa 1947.

These were the early days of light classical music, the stuff we now know as pops. There was a demand for original, recyclable background music — for radio dramas, commercials, newsreels and all kinds of broadcast filler — and Black was one of the guys who supplied it, in quantity. (In England at this time, Robert Farnon was the master of light music, writing scads of pieces with titles like “Jumping Bean” and “Peanut Polka” as well as plenty of canned “production music.”) Black had a diversity of taste unusual for the era. “Amazes Musicians by Switching From Jazz to Classics,” read one newspaper headline from 1937.

It was hard work. Reading scores, doing auditions, writing arrangements, supervising the purchase of instruments, tracking down Kim Deal conducting concert after concert. “It has been some years since Black has enjoyed a vacation from his many arduous and taxing assignments,” Ewen wrote. “A day of work does not end for Black until nine in the evening; but frequently Black is still hard at work at his office till well past midnight.” In 1936 and 1937, for instance, Black was doing “Magic Key” in Manhattan on Sundays and the Carnation milk program in Chicago on Mondays, and commuted back and forth by air for 58 weeks. Back then, remember, stewardesses doubled as nurses and planes looked like toy models (left).

In 1936 and 1937, for instance, Black was doing “Magic Key” in Manhattan on Sundays and the Carnation milk program in Chicago on Mondays, and commuted back and forth by air for 58 weeks. Back then, remember, stewardesses doubled as nurses and planes looked like toy models (left).

In a 1939 profile, Time magazine described Black’s flight hazards:

He was gashed and kayoed when bumpy air over the troublesome Nittany Mountains conked him against an overhead baggage rack. He once watched ambulances gather below him at Newark when his ship could not get its landing gear down. He weathered innumerable forced landings and is one of the few air travelers who ever landed on an airport backwards... Frank Black, who finds the lofty detachment of air travel just the ticket for writing arrangements, still likes to fly.

Even in the hospital, the guy worked like a dog. An NBC press release dated Halloween 1938 reported that Black “has been living in the Leroy Sanitarium in New York City for ten days and expects to stay another ten.” But instead of resting, he was “doing musical research and writing arrangements for the series of Great Plays heard over the NBC-Blue Network from 1:00 to 2:00 p.m. on Sundays.”

“It’s a great place to write,” Black said. “At last I’ve found a quiet place to work and I’m really accomplishing a great deal.”

Hang On to Your Ego!

He worked hard for the money, and by gum he got it. According to Time in 1939, Black was raking in $100,000 a year for his weekly “Cities Service” and “Magic Key” concerts and summer gigs with the NBC String Symphony. (Average wage for a college grad was then around $2,000.) As if those responsibilities were not enough, he was also expected to “oversee NBC’s vast music library, and dash off arrangements — popular or highbrow — which are the envy of the profession.” It wasn’t all symphonic bubblegum. In 1942 he collaborated with Edna St. Vincent Millay on the music for her dramatic poem “The Murder of Lidice,” about the Nazi atrocity that year in Czechoslovakia. In a statement, he advocated political engagement in the arts:

It wasn’t all symphonic bubblegum. In 1942 he collaborated with Edna St. Vincent Millay on the music for her dramatic poem “The Murder of Lidice,” about the Nazi atrocity that year in Czechoslovakia. In a statement, he advocated political engagement in the arts:

Black agrees with Miss Millay that now is no time for artists to withdraw into artistic ivory towers far-removed from a war-torn world. “The times,” he says, “make almost every one writing good music to stop thinking about the techniques of their art in order to think more about its content.”

He got his kudos. In May 1935 he collected an honorary doctorate from Missouri Valley College (you can be sure that every press release and puff newspaper column that followed diligently called him “Dr. Black”), and five months later was made an officer of the French Academy, “in recognition of his services to French artists and for promoting a wider knowledge of French music in the United States via radio.”

The honor was given in New York by Isidor Philipp, a well known French pianist and teacher. “The decoration which accompanied Dr. Black’s commission,” NBC announced, “consists of crossed silver palm leaves set in rubies.”

He published articles on American composers and cultivated eccentric theories. NBC sent out a flurry of releases in early 1934 about his idea for a “standing orchestra.” Black wanted the musicians “vertical” during the broadcast, believing that they “are at their best when standing as they fiddle and toot.” His quote:

“No violinist would think of sitting during a concert performance. What does he do? Why, he always stands! So, that’s what I intend to ask my musicians to do during this hour program.”

Frank Jeremiah had one major hobby: collecting rare musical scores. Over the years he amassed a big trove, and reading between the lines of NBC statements and contemporary accounts, one gets the sense that these delicacies might have functioned as a kind of tribute to the grand man, or even quid pro quo. Consider this anecdote in a slice-of-life release from NBC in 1938 about visitors to Black’s office at Radio City, where the good Doctor received solicitations for new music:

Not long ago a total stranger was admitted to Dr. Black’s office. He had with him an item he wanted to sell Dr. Black for his collection. The musical director looked at it and was amazed. It was a first edition of a mass by Schumann, published posthumously.... The item stayed with Dr. Black for study and investigation, and in a very few days the man received a check.

The release goes on to say that Black’s library includes “a first printing of the Kreutzer Sonata, a first printing of the original scores of Wagner’s ‘Nibelungen Ring,’ the full scores of Gluck’s operas printed in 1774 from woodcuts, a Lutheran hymnal dated 1784, the first music ever printed, and a first edition of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies.” Hmm, how many of those priceless items arrived during office hours from “total strangers” who might or might not have also represented music publishers? Just wondering.

Bad, Wicked World!

The trail starts to go cold in the mid-’50s. In his later years Black worked in light opera, Hollywood musicals and Broadway, but he disappears from the papers, which during the ’30s and ’40s had reported even his mundane real estate investments. Dr. Frank J. Black died in Atlanta on Jan. 29, 1968.

One positive light is that his collection of scores, which had grown considerably, found a home as part of a library at the Midland-Odessa Symphony in Texas. I have yet to find out much about this, but here is a paragraph that had been on Midland-Odessa’s website, now accessible only through cache:

[Robert G.] Mann was directly responsible for the 1968 acquisition of the Frank Black Music Library, one of the largest in the Southwest and remarkable in other respects.... The Black Library, occupying twenty-two steel cabinets and weighing five tons, has more than 3,000 pieces by 550 composers, including all of Beethoven’s symphonies and piano concertos as well as much of the standard repertoire. Some of the scores are original editions which are, for the most part, no longer obtainable. Many of the scores and parts have Toscanini’s notations for bowing and phrasing. The music of Rachmaninoff bears optional cuts in the composer’s own hand, and some of the Richard Strauss scores are enhanced by notes and comments by the composer.

Wondering why you’ve never heard of this Frank Black before? One clue can be found in NBC’s notes on that St. Vincent Millay project from 1942. Black clearly craved recognition, but he also seems to have enjoyed a certain amount of the behind-the-scenes invisibility that comes with radio. “If, after they’ve heard it,” Black said of the piece, “listeners say it’s a great poem, and if they don’t mention the music, I’ll know that I’ve done a good job.”

15 comments:

He looks like he's made of wax.

Pretty amazing. I wonder what he did do in those lost later years? Perhaps travelled the world in search of rare musical scores, as a sort of Indiana Jones? Fan fiction, anyone? It does sound like his collection would fit in with the Area 51 glimpsed in the Jones movies.

My taco has been kicked by this amazing research!!

Old Frank Black had a song called "Jumping Bean"? New Frank Black has a song called "Jumping Beans"! Coincidence?

Almost!

"Jumping Bean" was written by Robert Farnon, not Dr. Frank J. Black.

Listen to Farnon's "Jumping Bean" here.

And what's the deal with another Reid Paley. Another coincidence?

I wanted to thank you for posting this information on the Internet because Dr. Frank Black was my late grandfather. Unfortunately, I never had the opportunity to meet him. He passed away two years before I was born.

My name is Evelyn or “Eve” Black and I was born on Sept. 18, 1970. My father, Frank J. Black, Jr., was his only son. I'm named after my grandmother Eve and the wife of the original Frank Black.

Eve,

Thanks for reading, and for leaving your comment! I'm thrilled to hear from a descendant of the great Dr. Frank Black.

I have a good deal of research on your grandfather, which I'd be happy to share with you if you like. My email is listed on the right-hand column of this blog.

Best,

Ben

Hello All, My father was a reveler in the late 60s early 70s and left us about 9 milk crates full of original hand annotated Frank Black scores. I am wondering if there is any interest out there for these, It is a very large collection.

If you have any ideas, leave a note here I will check back,

Thanks

CB

Hello Eve, CB and Ben, My name is Tracy Jordan and I am the great, great niece of the original Frank J. Black. Eve, my Mother always spoke about "Uncle Frank" and as my daughter is doing a family history project for school, we are uncovering all kinds of information. I have a lamp that Uncle Frank gave my Grandparents as a wedding gift. I also have letters that Evelyn wrote to my Grandfather as a young boy. BC and Ben, I would be very interested in chatting with you as well and about the history you have of Uncle Frank. How can I reach any of you?

Hello, It is Chris with the 9 crates of Frank Black annotated music. Sorry it has been so long since I have checked back.

Leave an email address here and I will send you some pictures of his music. I have pulled a few out and was very interested as someof them had notes to and from George M Cohan. Some of this stuff is real history. Like Depression era songs and arragements.

Pretty interesteing stuff...

Let me know and I promise I will check back here more often.

Hi,

The email address is to the right. (blud at pinkyviolence dot net)

Send and I will hit you back!

Ben

Chris, Ben and hopefully Eve,I apologize for not checking back sooner. My email address is jordantracy@yahoo.com I am very interested in any information you have on my Great Uncle. Thank you, Tracy

I would love to talk to Evelyn. Evelyn has a sister named Tracey Waterman in New Jersey!

Post a Comment