“Where do you take it? You don’t take it. It dies.”

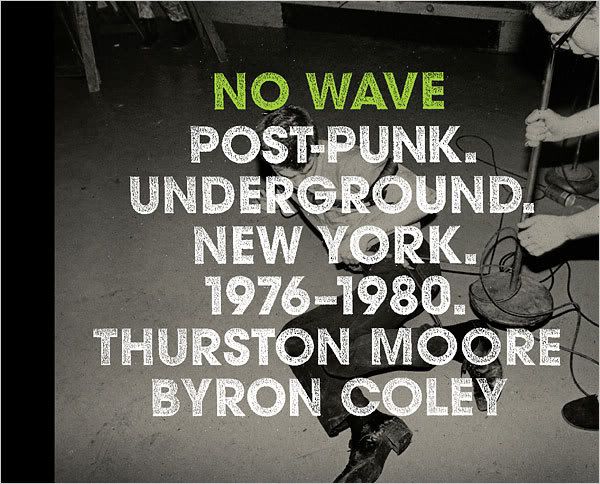

I have to admit that part of the reason I wrote a story about the new No Wave book by Thurston Moore and Byron Coley was simply to have the opportunity to talk to Moore once again. I’ve interviewed him a few times over the years and it’s always been enlightening and refreshing — his knowledge is immense, of course, but I also find his passion and engagement inspiring. Moore turns 50 in July, and what he shows me is that that’s not old at all. Hearing him detail gigs from 1978 as if they were last week is another reminder.

Over the next week few weeks, I’ll be posting interviews I’ve done with Moore, including talks about China and noise rock. Here’s the most recent one, on No Wave. We spoke by phone on June 2.

What was the genesis of this project?

It was an idea that Byron Coley and I had for a number of years. When I first met Byron it was in the early ’80s, when he was living in Los Angeles. He used to live in New York in the ’70s and he was a roadie for 8-Eyed Spy,* which was Lydia [Lunch]’s band after Teenage Jesus and Beirut Slump, just post the original No Wave scene. He was sort of hanging around that scene in New York in the ’70s, and I was around as well but I didn’t really hang out with the same people. He was a little more intimate with the figures in the book. I was kind of a loner on 13th Street, although I lived on the same block as Lydia during the Teenage Jesus days. I didn’t really pal around with her, which was probably a saving grace on my end.

Would you see her at the bodega or anything?

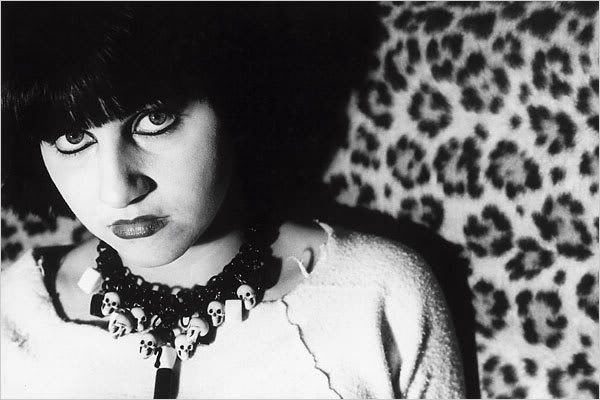

I would see her certainly on the corner of 13th and A at the laundromat there, and was always sort of taken aback by her because she had a nose ring. In those days, pre-modern primitive, it was shocking to see a young Caucasian girl on the street with a nose ring. So she was kind of fascinating to me, although I was extremely wary of her because I had only known her through her interviews, like in the SoHo Weekly News, where she was completely denouncing all that was sacred in the New York punk rock scene — Patti Smith, Television, etc. Which was completely insane, because punk rock was all about denouncing everything that came before it, and all of a sudden here was this 18-year-old girl in the SoHo Weekly News just trouncing our vanguard. [Laughs.] So I was a little confounded by her.

So she had some notoriety already?

She had some notoriety first of all because of the name of the band. Second of all people sort of knew about her because her personality was so brazen. I remember seeing the name Teenage Jesus and the Jerks in the Village Voice in a Max’s ad and just thinking, “That’s the most ridiculous name ever — what’s next?” And I didn’t really think anything of it. Then I kept hearing little things about it, and then I realized it was this girl Lydia, because she was in the newspaper. And then there was an interview with Joey Ramone in Hit Parader magazine, I believe, where he was asked who his favorite bands were, and he said Suicide and this new band Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. And I thought that was such a validation that I started taking it seriously.

But I didn’t have any money to go see these bands. Unless you were friends with them you probably couldn’t get in free, and I couldn’t really afford the $3 or $4 to get into CBGB or Max’s, to see a band that was my age living on my street doing something that I was doing anyway with the band I was playing with. If I had any money I would have used it to go see the Ramones at Hurrah’s or something, or at least buy some cigarettes or stuffed cabbage, [laughs] which was kind of the lifestyle. So I never saw Teenage Jesus, but I saw [Lydia] on the L train, like when I was going to work or something, and she would be standing there going God knows where. In retrospect I certainly wish I had seen them. I actually went to Teenage Jesus at CBGB and I didn’t go in through the door. I decided to go home instead, which I regret to this very day.

You got to the venue but didn’t go in?

I was there with a friend of mine and we were going to go in, and I was like, ah, I really can’t spend the three bucks. And I walked home, went to bed, and that was about it. It was early ’77 and I was just living poor on 13th Street and Avenue A. But that was not atypical. That’s just the way it was. You would sort of save your pennies up and go see the Voidoids or something. Sometimes you could sneak into these places. But the first time I saw these bands was really when they played for free at a loft gig.

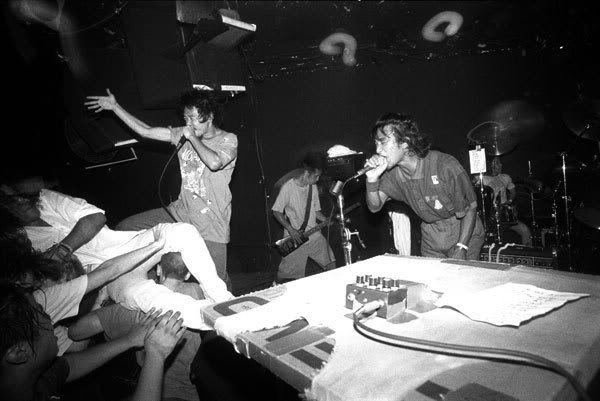

The most specific moment I remember is going to the X Motion Picture Magazine benefit that Arto Lindsay and Seth Tillett put on at the Millennium. Everybody on the downtown art scene went to that. I went with all my artist pals. And there it was. Teenage Jesus at that point just didn’t play; Mars didn’t play because I think Sumner Crane didn’t want to play for free. But it was this total landmark event for that scene. That’s where I saw Theoretical Girls and the Contortions. That was supposedly the first Contortions gig where James [Chance] really took it upon himself to physically interact with the audience in a very negative way. And it was great. I was watching it in the buzz of this room, just thinking, “This is kind of fantastic.”

How old were you then?

I was just 20, probably. I was born in ’58, and I think the X Magazine thing was either late ’77 or early ’78.**

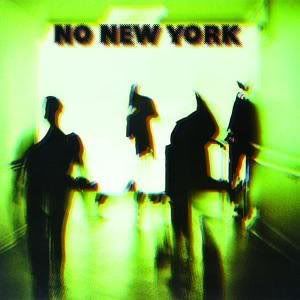

Everybody was into radical music on the scene, but our concept of it was Dead Boys, Ramones, Patti, Television, Voidoids. There were a lot of new, younger bands. I was in one of them, and we were very Talking Heads-influenced, because the guys I was playing with came out of the Rhode Island School of Design, the next graduating class after Byrne. So that was sort of our thing. But these guys weren’t referencing anything that we had any awareness of, really. It was such an anti-music gesture, but it was completely thrilling. It was very guitar-centric, even though James played saxophone and Adele Bertei played keyboards. But there were really sick, weird guitar situations going on, with Pat Place’s constant slide guitar drawing up against Jody Harris’s guitar in the Contortions. [Garbled comment about Lydia Lunch] ... but I knew Pat was coming out of her. That was her inspiration, page 1, was Lydia’s slide guitar playing, which on record is ferocious. This is one of the great unheard periods of music — even the record that defined the genre [No New York] is notoriously difficult to find.

This is one of the great unheard periods of music — even the record that defined the genre [No New York] is notoriously difficult to find.

There’s lots of live tapes that have never surfaced that I’ve heard that would really change that situation. But dealing with the propriety of this music is a little difficult. I was really surprised when I was doing research for this book how little of the live documents exist on the Internet for download. But there are some very significant documents — the pink Teenage Jesus 12-inch is very good as far as showing what that band sounded like. No New York, despite people’s qualms about how it was executed, has fantastic tracks on it; specifically, the Mars tracks are wonderful. And the Mars stuff been issued here and there on different labels. There’s a few small labels that have put stuff out. Acute Records put out the Theoretical Girls record that was primarily Jeffrey Lohn’s side of the story of that band, as opposed to Glenn [Branca]’s. Glenn has released his side of the story quite a bit through ... [garbled]. Lydia is always documenting Teenage Jesus stuff. Atavistic is putting out a complete Teenage Jesus CD compendium this month.

Did it take 30 years to properly document it?

The only person who doing it then was Charles Ball, who was pals with Terry Ork. Terry Ork put out the first Television 7-inch, and the Voidoids. This was going on so currently with the first generation of punk rock it’s a little misleading for us to call the book No Wave. Post-Punk, because it’s really not post-punk; it’s happening at the same time as punk. Mars started in 1975. Their contemporaries were Patti Smith and Richard Sohl. It’s post-punk only because it’s music that could not have happened without the direct influence of punk, but it sounded nothing like what people knew of punk rock. Certainly Mars did not, even when they were called China. I remember seeing the name China and just thinking it was another new rock band at CBGB. Who would go see that? The fact that Lydia went to see that as a 16-year-old and said, “OK, this is what I want to do, this kind of music” — this completely bizarro sound that Mark Cunningham and Connie Burg and Sumner Crane and Nancy Arlen were doing.

This scene was small by any measure but in the book you narrow it down even further to sort of the bare essentials.

Oh yeah, it was a very tiny thing. It was a little, blippy scene. But you know, at that time even the punk rock scene at CBGB and Max’s, it was a downtown community. There was no real media eye, there was no Internet, we weren’t on TV. It was getting written about in London in the NME and therefore the rest of the world sort of saw it. But it’s funny — When Patti Smith came back on the scene years back and she started doing these events, one thing she said is that what’s changed is that everybody is in effect, everybody’s there — MTV, VH1, “The Legendary Divas” and all this sort of thing. She was so confounded by how many people were on the scene. Whereas back then you sort of knew who everybody was. You knew who the writers were, you knew who the photographers were. It was a handful of people.

That speaks to influence this music had.

Yeah, punk just obviously blew up and became involved with everybody’s consciousness. But No Wave — [Laughs.] We like the absurdity of how small it is. We kept our parameters really tight. There’s lots of adjunct activities that were happening around the No Wave scene. But we really wanted to keep it super tight as far as who were the prime instigators and the ones who really developed what is known as No Wave in New York City. We needed a cutoff point, and we cut it off as soon as anybody plays any semblance of rock ’n’ roll. Any kind of traditional aspect of rock, it’s over. When Lydia starts 8-Eyed Spy, forget about it. Or Pat Place starts Bush Tetras, it’s over. Arto Lindsay in the Lounge Lizards — no.

That’s how people progressed. They did sort of take on more traditional — it’s a sophisticated take on traditional aspects of rock music. [With] No Wave there was no take on rock music, except for, like, electricity and the instrumentation. But what they were playing, it was over before it began. It came out of the gate finished. It wasn’t even about development. The only band that maybe developed was DNA, because they lasted until like ’82. But what they were doing with classic lineup with Arto and Tim Wright and Ikue Mori, it had created its own standard immediately. It didn’t develop like Talking Heads developed.

There’s a quote in the book from Eno, who says he was attracted to it “as an art historian” because it resembled previous artistic movements where there was this explosion and then immediate implosion.

He knew it was this really interesting finished piece that was happening. Where do you take it? You don’t take it. It dies.

Was that clear even while it was happening?

No, because while it was happening nobody even knew that it was called No Wave, and as soon as it started becoming called No Wave it was already in sort of a dissipation mode. The first time I saw name [the term] No Wave was not in the SoHo Weekly News when Roy Trakin was interviewing Lydia, at least I don’t remember. I remember seeing it spray-painted in front of the CBGB Second Avenue Theater, which used to be the Anderson Theater, where the Yardbirds played. Hilly and his wife had opened up the Anderson Theater, renamed it CBGB Second Avenue Theater and attempted to have a bigger space for bands. I remember going there a couple of times and seeing Blondie and Patti Smith and Richard Hell. It was fun, but you knew it was a disaster because it was a seated venue and people were just smoking pot in there and drinking, and the fire marshals had their eye on it. It just couldn’t last, and finally they closed it down after month or two. And somebody had spray-painted on the front of it, “No Wave.” And I thought, “Oh, that’s kind of clever.”

Did you understand what it meant?

Well, no. I mean, punk had become new wave, and we were all sort of laughing about that, because it was this attempt to sort of commodify it and make it digestible. And then all sudden it got bigger, and Hilly had a theater, and then it was closed. And someone had written “No Wave,” and I was like, “Wow.” And then that’s when I started hearing more about those bands. So that’s my take on where that word came from: somebody had scrawled it on Second Avenue. But other people have different ideas about where that term originated. In retrospect, after doing all this research, I think it probably did come out of Lydia’s mouth. Because it’s certainly something she would say.

It’s interesting to hear you describe all of this as an outsider looking in, since you were there and most people would think of you as being intimately involved with this world. I was curious about anything that was happening in the neighborhood. I was a typical 20-year-old ’70s kid living in New York by myself, wanting to be in a punk rock band. But what resonated more with me was probably the downtown artists scene, as opposed to the leather jackets and safety pin scene that was not really that prevalent in New York to begin with. There was definitely this CBGB-Ramones-Dead Boys scene of kind of street-trash punk, but I didn’t go for that so much. I was more into going to Canal Jeans and buying 99-cent skinny lapel jackets [laughs] and hanging out the Mudd Club — or trying to get into the Mudd Club, actually.

I was curious about anything that was happening in the neighborhood. I was a typical 20-year-old ’70s kid living in New York by myself, wanting to be in a punk rock band. But what resonated more with me was probably the downtown artists scene, as opposed to the leather jackets and safety pin scene that was not really that prevalent in New York to begin with. There was definitely this CBGB-Ramones-Dead Boys scene of kind of street-trash punk, but I didn’t go for that so much. I was more into going to Canal Jeans and buying 99-cent skinny lapel jackets [laughs] and hanging out the Mudd Club — or trying to get into the Mudd Club, actually.

So that was more my milieu. But I only knew a few people. I moved to town knowing one person. Lydia tells the same story, coming to town and not knowing anybody except for recognizing Wayne County, who she was a pen pal of. Which I totally related to because I had written to Wayne County as a teenager too. [Laughs.] You know, “Dear Wayne.” He had a column in Rock Scene magazine, “Tips from Wayne.” So you’d write to these people. I remember writing to Lenny Kaye. He had a column called “Doc Rock.” So I really related to Lydia after I found out that she did the same thing. But she was far more assertive than I was. She came to town and would go up in people’s faces, saying, “I’m here, let’s get this thing going.” I was a bit more shy, more reserved.

So this is the third book in about a year that covers either No Wave specifically or similar periods in the history of downtown New York —

Marc Masters wrote a book that came out on a U.K. publisher, which takes sort of a different tack. He covers some of same ground in his interviews as far as history goes and the connective band stuff, but he basically takes the tack of following how the recordings document the scene. We don’t really talk about the recordings so much beyond No New York, which we wanted to get into because there was so much controversy about how it was made, and how it dissected the scene. Lydia told me when I told her we were doing this book, “Well finally someone who was there is doing it.” Which sets us apart from any other No Wave book, is that we were participants. So we really did have a feel for it.

When we pitched this book, it was something we were just going to do ourselves independently. And I had been talking to an editor at Abrams who I work with, and she said that Tamar Brazis, an editor at Abrams who had edited the CBGB book, that her next project was a book on No Wave. And I was like, “You’ve got to be kidding me. I need to have a meeting with her immediately and pitch Byron’s and my concept of what this book should be.” So I had Byron come down from western Massachusetts, and I think we kind of blew their minds a little bit, because we just had it completely detailed and laid out what this book needs to be.

I think the [publisher’s original] idea of No Wave was very broad, as opposed to what we thought it was. Which was like, it wasn’t broad at all; it can be looked upon as broad in its influence, but what it really was, as you said before, it was a little clique of a scene. And we wanted to portray it realistically as it was: as these people, these East Village habitués, the SoHo scene, and then these people who would sort of cross the camp geographically. Specifically people like Jim Sclavunos — who’s Mr. No Wave, [laughs] and who will be in town playing with Teenage Jesus for their one and only reunion show, on Friday the 13th. Which is going to be completely crazy. Of all the bands to get together to do a reunion, I can’t think of anything more far out than Teenage Jesus and the Jerks — even more so than the Stooges.

Was that at your prompting?

Oh yeah. I was visiting Lydia — she lives in Barcelona — and she had started play guitar again. She hasn’t played guitar for ever. She did some recordings with Halo of Flies, the Minneapolis band, these insane recordings. They’re great — some 7-inch just came out, she’s doing vocals.

I didn’t know Halo of Flies existed now.

Yeah, they’re sort of back. They just sound so damaged now, and she sort of adds to the carnage. And so she was really into playing guitar again. She was very hip about the book. She really gave us her time. [I told her] we’re going to have this gallery event that coincides with the publishing of it at KS Art on Leonard Street, and I’m going to have some music at the Knitting Factory afterwards, and you know what would be completely wild is if Teenage Jesus played one gig. And she said she’d do it. As long as I took care of it, she’d do it.

And you got James to do it?

Sclavunos? Yeah, he played bass [in the original band] but he will be playing “drum.”

Actually I meant James Chance.

Oh, James Chance. He’ll be around.† He was in the original lineup of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. The only other performer is Information, which was one of the bands that did cross over to the East Village/SoHo scene — Chris Nelson.

So who will be there performing at this Teenage Jesus show?

Lydia, James Sclavunos, mystery bass player,‡ [laughs] and I think maybe Chance will play one song with them. But you gotta realize, these songs are like 47 seconds long. [Laughs.] Lydia is rechanneling the hate. Teenage Jesus and the Jerks were not a band you would see to have a good time. Even though a lot of people remember those shows fondly, they were a very mean band. The whole thing was a total affront to any congeniality an audience and a band would have with each other.

What was the publisher’s original idea for the book?

Downtown-New York-’70s kinda nightlife, No Wave. What could it have been? Probably Contortions, DNA, Basquiat, Burroughs and Blondie, Debbie Harry. Which is interesting because all of those people have associations with the No Wave scene. Debbie Harry, I think, loved Lydia and what she was doing, as did Chris Stein. Basquiat certainly was at those gigs, and bouncing around. He was always at Tier 3, he was always at the Mudd Club. Madonna was around, for God’s sake; she probably saw a Contortions gig or two. I tried to get a blurb from her, but I don’t know if the request ever got past her management’s desk. I did get a blurb from Bowie, that was kind of hip.

There was this highfalutin nightlife scene going on in New York, for what it’s worth. I think that what the editors initially thought a No Wave book would be was that real nefarious subterranea of downtown nightlife and the music scene. But I don’t think anybody could really identify it for what it was specifically. We could. We just sat down and gave them the game plan. We said, “These are the bands that are, that define No Wave; these are the events that define it; and these are the parameters.” That is it. Once it leaves these parameters it becomes No Wave-influenced, or it becomes something else. But as far as what defines the actual New York No Wave music scene, it’s these bands, these artists, these filmmakers, boom — and it’s over. It’s a finite scene, so it was really fun to deal with it as such.

Publishers usually want to sell books. Expanding the scope a bit would have brought this to a much bigger audience.

It also would have diluted it. And we sort of gave that argument in our editorial meetings. We met with the sales department, and we said, you know, there are figures in this book that have more cultural awareness than the primary subjects. Iggy is in the book, and Debbie is in the book, and Basquiat shows up in the book. Those weren’t bones we were throwing the sales department; they really do exist in the story. But we didn’t want to force that. And to the credit of Tamar at Abrams, she really let us go with our vision on this. It’s amazing that a publishing house as commercial as Abrams let us do this.

The black-and-white coffee table book treatment has the effect of enshrining artists and historical periods. Is it finally time for Lydia Lunch and James Chance to be on that same plane of New York bohemia with the Beat poets and Dylan?

Black and white made so much sense, because black and white was such a definite shade of what was happening on the scene then. It has this kind of noir take on it. Certainly there was color, but it wasn’t like the B-52’s or Blondie. That scene had such a rich archive of visual ephemera and materials, and the way it presented itself, the way the musicians presented themselves — they were so removed from the classic rock figures, not only in the rock ’n’ roll tradition but in the punk tradition, as nascent as it was then. You certainly had the ugly beauty of Johnny Rotten and Joey Ramone going on, but this was something else entirely. This was total weirdo nerd style going on. Arto was the last person you would think of as a guitar hero onstage. But he was fascinating because of that. And Lydia was not in any sense of the word what you would consider a typical female diva, even by punk rock standards. But she was completely alluring. As was Pat Place, who was this completely androgynous creature with the Contortions.

So the way they presented themselves visually, and the way the photographers were photographing them was to us a real treasure of an archive of a New York City aesthetic that was part of the lineage of downtown bohemia and Beat culture, and the radical counterculture of even the Peace Eye bookstore and that era of hippie, or something. So we really wanted to show that, and we wanted the book to act as much a book for the photographers. I think of Godlis and Julia Gorton, Lisa Genet, Stephanie Chernikowski — these people were shooting these bands at the same time they were shooting Patti Smith and the Ramones and Television. They knew these bands had an amazing look unto themselves.

There were so many more pictures we could have used. That was the hardest thing about making this book, excising photos for editorial sake, and the fact that there are archives of photos that people have who aren’t professional photographers. A few of which we used, but there’s quite a bit of those that exist in private collections that are not in this book, that are amazing. And there’s a lot of other ephemera — fanzine and flyer ephemera that could have been rife in this book.

Why now? Is there an element of nostalgia for a pre-gentrification New York?

A lot of musicians and artists — I mean fine artists as well as design artists — are very curious about that period. And because of the images that they do see, in old periodicals from the ’70s, when they look at old New York Rockers and such, I think they want to know more about it. And with bands like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Rapture and what have you referenced as like a new No Wave kind of thing — which is kind of great in a way, except the big difference is like, in the original No Wave bands nobody knew how to play. Even though the Contortions could have gotten funky out of the gate, because they wanted to be this kind of funk thing. But so much of the band didn’t know how to play. Pat Place didn’t know how to play guitar. They just put it on her, and she saw Lydia play, and she got a slide and played. James knew how to play the saxophone. If you hear early live tapes or see early live Super 8 footage, they just sound like wall of cacophonous chaos. And it’s great. They did distinguish themselves as time went on, becoming a very amazing damaged funk band, but at first it was this blitzkrieg.

There’s a great picture in the book where there are two people playing guitar in front of a bunch of people in an art gallery or something, and the people near the front have their hands over their ears, and they really look like they’re in pain.

That’s one of the shows at Artists Space. There was a series of shows there in ’78. That’s Tone Death, which is Rhys Chatham and Nina Canal and Robert Appleton. Again, it’s not a huge audience either, is it. It’s just the SoHo scene and some people from the East Village No Wave world, cohabitating in this world. You can see Barbara Ess poking her head through the door. It makes you wonder what’s coming out of those amps. They’re not using huge amps or anything; they’ve got little Polytone amps. But it’s enough to completely mess with this audience’s head. [Laughs.]

Thanks, etc.

* Coley says he traveled with the band some but was never a roadie.

** According to a flyer in No Wave, the show was on March 11, 1978. Moore would have been 19 then, and Lydia Lunch 18.

† He was there but didn’t play (at least not at the early show).

‡ The “mystery bass player” was Moore.

Next: China (the country, not the No Wave band).

Links: Weasel Walter’s New York No Wave Photo Archive; Laura Levine’s shots of the street scene outside the book party/Teenage Jesus show; blog for Marc Masters’s No Wave book, and excerpts; Perfect Sound Forever’s interviews with Lydia Lunch and Robert Quine; my obit of Quine from 2004.

Back catalog: Al Green, Lou Reed, M.I.A., Stew.

2 comments:

I'm gonna whoop yo ass when I git back from India...aint no no wave up in here!

great interview though.

Post a Comment