‘Only comedians can talk about death, life, God and Virgin Mary. If I was a tragic actor, I couldn’t allow myself. But I can talk with death in person because I am a clown.’

I was extremely fortunate to interview Roberto Benigni recently for a piece about his show “TuttoDante,” which he is bringing on a short North American tour.

I was extremely fortunate to interview Roberto Benigni recently for a piece about his show “TuttoDante,” which he is bringing on a short North American tour.

Here Benigni is best known, of course, for “Life Is Beautiful.” But he is also an accomplished Dante scholar. He has been giving public readings of the Divine Comedy in Italy for years, and since 2006 “TuttoDante” has been his main gig, seen by millions. In it he riffs on history, language and politics, and recites a canto from memory, in Italian. The tour opens in San Francisco on Tuesday and comes to New York on Saturday.

I met Benigni on May 21 at a hotel off Times Square. He was charming and uproariously funny, as you’d expect, but he was also one of the warmest and most down-to-earth celebrities I’ve met. He began by asking about my Italian heritage. I told him that my grandfather was born in the Aeolian Islands, and he said that once the mayor of Vulcano greeted him with a Sicilian marching band.

My tape begins in medias res ...

Do you get that kind of reception everywhere in Italy?

No, not like with a band. But in Italy, you know, people recognize me and they see me like a friend. They touch me. They don’t say, “Oh, Mr. Benigni ...” No, they touch me physically. They want to taste, physically, my body. When you touch somebody, it’s always a sign that you really like him.

You invite that, don’t you?

I use the body a lot. I hug people, I embrace, I want to touch. This is why I like so much to be on stage. That’s why I like the Divine Comedy, too, because the book is alive. For Dante Alighieri, the body is very important. It’s the only real body in the reign of shadows. So continuously he says “my body, my body, my body.” Also, in the Gospels the body is important. The resurrection is a sign of the body for Jesus Christ. This wonderful body, resurrected. “Touch me,” he says to St. Thomas, “touch me.” The body is as important as the soul. So it’s a sign of allegria, a beautiful thing.

OK, we start the interview. Thank you to be here again.

I’m honored to meet you. So tell me, why did you decide to bring “TuttoDante” to America?

My God. The United States is the goal for every show, of course. The United States is the show. In Europe and in Italy I decided to start very low-profile. I started three years ago in Patras, in Greece, just to try to do something that I loved very much. And the reception was so wonderful that I decided to continue, just to try. I was thinking, “Maybe I am going to lose some audience, but I’m doing what I really love.”

The Divine Comedy is one of my favorite things. So beautiful, full of image. It’s really a show. In my mind it is the most marvelous poem, the most glorious imagination of modern poetry. It’s like a friend to me. Dante Alighieri, you know, I really want to touch him, to call him by phone and say, “What are you doing tomorrow?” Because when I was reading the Divine Comedy, it was Dante Alighieri reading to me. This man, he knows me profoundly, more than any other body. So I said, this is a real friend, a close friend of mine. I was just going to ask the phone number for Dante Alighieri, to take a walk with him: “Hey Dante!” I really like him. He’s somebody we have to thank forever, for eternity.

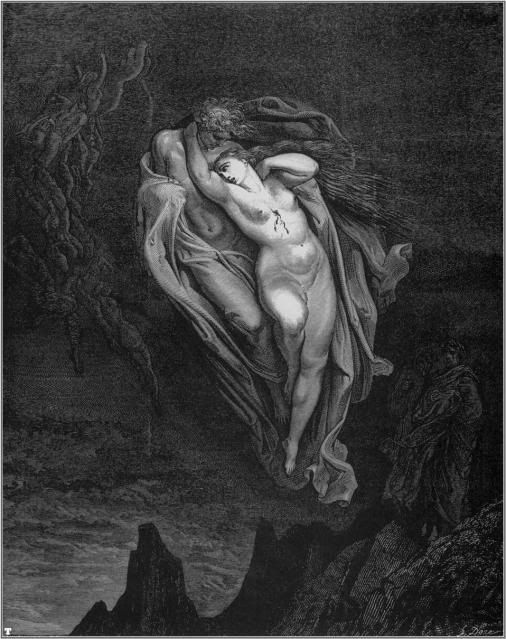

So I decided to make it in Italy. And much to my astonishment, the audience increased, like for a rock concert. They were following me with Vespas in Florence. [Here I take out a DVD of one of his performances in Italy, from a series distributed through the newspaper La Repubblica.] Which number of this? The 11th. This was in Florence. You see the amount of people was like 6,000. The average of every show we did in Italy was 6,000 or 10,000. Sometimes in Siena and in Padua it was about 40,000 people. It was incredible. It was like for Springsteen, [with people] asking me for some cantos: “Hey Benigni! When are you going to act Paolo and Francesca, Count Ugolino?”

Were they there for Dante, or for you?

I cannot compare myself to Dante. But the way I present Dante, maybe the two things together: Benigni and Dante. I feel embarrassed to say these names together, of course. But there is something, a spark. Because I think people now need somebody who talks simply about life and death, about our destiny. These are the simple questions that everybody, at least once in a day, we have to ask ourselves. And Dante does this. He talks to us simply. It’s like to [look] in an abyss and see our secrets of life and death. And also because the goal of the Divine Comedy is beauty. The beauty. It is something that you present, like a peach tree. It’s modern, it’s ancient — what can you say about a peach tree? It’s a peach tree.

Why is “Inferno” the most popular part of the Divine Comedy?

I also did “Paradiso” on TV, the last canto, the most difficult, we can say incomprehensible. And there was the maximum of audience, 50 million people watching the last canto of “Paradise.”* They weren’t expecting such an enormous number of people watching TV for the last canto. It was really incredible. But I must say that “Inferno” is the most popular because it’s especially profound. It is unequaled for imagination, for emotions, for image and sound, like a movie.

In “Paradiso” there is some tercets, triplets here and there — insuperable. “Purgatory” in my opinion is the perfect cantica. It’s really mature. And the profound “Inferno” is unrivaled for the strength — la forza, the force — of the creation. Insuperabile. That is why I choose “Inferno” for this tour, especially Paolo and Francesca, which is the first circle of hell. And when I am here in New York it can remind me a lot of “Inferno,” in a good way ... [Chuckles.]

We know how to sin.

So it’s really very popular, and I decided to continue, and to come to United States. And now I am full of emotion because it’s my first time in United States with a show onstage. And you know, my English is not acceptable. It’s really revolting. First I decided to make the show in Italian, but you know it was something ... Now I don’t have time, and I am too old to study English in a correct way. So, as Dante did, I try to invent a new language. It is incomprehensible. [Laughs.] But anyway it is so healthy to talk about incomprehensible things, as Dante did. It’s very good for our health to talk about something that we cannot understand. We really need this. Like why need food for our body, this is a really wonderful food for our soul. Nobody talks about these kinds of things. Church in itself, they don’t talk about this. So we have to thank Dante that we have opportunity to talk about this kind of thing. And in New York, you know, this is the center of paradise and hell together.

But anyway it is so healthy to talk about incomprehensible things, as Dante did. It’s very good for our health to talk about something that we cannot understand. We really need this. Like why need food for our body, this is a really wonderful food for our soul. Nobody talks about these kinds of things. Church in itself, they don’t talk about this. So we have to thank Dante that we have opportunity to talk about this kind of thing. And in New York, you know, this is the center of paradise and hell together.

There are some things lost in translation, of course. But when I recite the fifth canto by heart at the end, it’s important to listen. We need to have the nerve to understand why a man with a big nose 700 years ago had the heroic shamelessness to write. Really this is the most daring, bold poetry ever. In 2,000 years of Christian poetry they never surpassed this. They never produced such a scandal of beauty. Never, never, nobody. Our planet is too little to allow the luxury of ignoring Dante. There is no other poet that put the human suffering and the human conscience at such a high point.

You said the poem is marvelous, glorious, heroic — but you didn’t say funny.

The title is Comedy. They added “divine” in 1555, but Dante called his work Comedy. Just La Commedia. Using low style. And he uses a lot of comic style. If you read the 21st, 22nd and 23rd cantos, it’s like Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, or Totò and Peppino in Italy. It’s like a farce. You really laugh. And there is the occasion to laugh a lot, especially in hell, in Inferno. Because in Purgatory you can smile, and in Paradise you don’t laugh — you just stay there to watch. How can you laugh when you see a rose blossom? You stay there in a stupor. And the stupor is the commencement of art. When you finish reading the Divine Comedy there is only one word you can say: incredible. When you read Shakespeare or Walt Whitman or some others, you can say, “This man is a genius; he is a genius and he’s really talented.” But for Dante, no. For Dante there is only one word: incredible.

Now I want to tell you, I don’t do commentaries or notes. I am not a literature or critical man, or a professor, or an emeritus professor. I am a showman and a comedian above all. So I am doing the show as a comedian can do it. Respectfully. But still I am a comedian, so I have to try to render it in a way popular and understandable. The show is very simple. There is only one man there, with a reading desk. We need the conversion of our imagination. Dante forces you to imagine everything. The stage is really full of devils, objects, animals, insects, monsters — and our soul is full of this. This is the stage. It is like a poem embodied with all this. And it is so deeply, psychologically spiritual. This is the strange thing, the strange mélange, the strange link that only Dante could dare to try things like this.

In the first part of the show I am, repeat, a showman. So I am improvising. That’s why I cannot use subtitles, because I never produce the same show. And also because everything Dante says is concerning us, very specifically. The first part of the show, I repeat, is about our times. Although all the great creators, they don’t write for their times. They write for everybody, always. They write in an eternal present.

Italians grow up on Dante. But do you think it will be difficult for Americans to grasp the details of the Comedy? When it comes to Francesca da Rimini, Guido da Montefeltro or whatever, doesn’t all that take more explanation?

It’s universal. Talking about Dante as [just] a Christian or an poet Italian poet would be to abate his universality. It’s not important to know where Ravenna is. Who cares? When I read Melville I don’t need to understand what kind of sea. No. Every single word of his book belongs to me. When you see “The Bicycle Thief” — Naples, Rome, who cares? It can be anywhere around the world. It’s there to convey the sentiment. Great poets, they invent sentiments. Everything in the Divine Comedy is expressed with emotion. And emotions are the same around the world. If we think like this, it’s thanks to people like Dante.

The image of Eros is changed after the Divine Comedy. The relation with women is changed also, because a character like Beatrice is insuperable. We cannot understand — unfathomable. All we know is the image of a girl. It is written in the eyes of this girl: “You are eternal.” Dante is really first the modern poet. He said that we are the masters of our life and death, of our destiny. Before Dante, no — we are guided by gods, like in Homer. With Dante starts the modern poetry, the modern human being.

In the first part I also talk about Berlusconi, which to convey is very easy. [Laughs heartily.] For Berlusconi the entire hell is not enough. We have to build another personal circle for Berlusconi. You know, Berlusconi, he passed a lot of laws just for him, just for one man. So maybe his punishment could be to build for him a circle in hell, but very personal, just for him: “Eh, this is just for you, Mr. Berlusconi!” [Laughs.] Or if I could do in movies this wonderful book, which is impossible, but as a comedy, a parody, I would like to find Berlusconi in every single circle. The lustful: Berlusconi is there. Fraud: Berlusconi is there. Or the corruption: Berlusconi there. Liars: Berlusconi is there. [Laughs.]

People say you used to be a lot harsher on Berlusconi. But it doesn’t sound like you’re any friend of his.

I am a comedian. And my duty is to joke with the people who have a lot of power. Berlusconi now in Italy, he has no power — he is the power. So it’s a duty for me now.

Are you still as political as you used to be?

Everything we know is political, directly or indirectly. Sometimes I am directly political, especially on TV, or on stage. So, I repeat, it is [slightly mocking tone] my duty to protect citizens from the powers, the governors. And for a comedian, Berlusconi is really a wonderful thing they gave me. “Benigni, you are very lucky you have Berlusconi ...”

We had Bush.

[Laughs.] Very good for comedy, Bush. And they were very good friends, Bush and Berlusconi.

Is Obama funny?

No. It is not the right word for Obama. I like very much Obama. Obama is really an illumination. Obama gave back to the United States the image that we had when I was young. But I believe in image. And the image of Obama is the image of beauty, in the poetical way, in a metaphorical way. It’s really a wonderful image.

He’s in the “Paradiso”?

He’s in “Paradiso,” for sure. But I like him because he is a real man. “Paradiso” but with some “Inferno.” That is good.

He smokes.

He smokes. And I don’t like just saints in Paradise; it’s very boring. So yes, some “Inferno.” Very good. That’s why I like him. He smokes, he plays cards.

Why did you decide to do Canto V on this tour?

Canto V is one of the most popular, very loved by Dantists, and above all by boys, ragazzi. [Benigni’s manager corrects his translation: “kids.”] They love it because he is talking about sex, passions and love. Telling us the roots of love. Can we fall into hell if we love somebody? It is a metaphor for the hell of our lives. If we take the sentiment in the wrong way, our entire life [becomes hell]. But Dante is never talking about love in a schmaltzy way. [Makes mushy sounds.] Very tough, very rude. No, not rude — rough. Love is the sentiment that moves the sun and the other stars.† So it’s a sentiment that scares you. And the fifth canto is the first circle of hell. So it’s very good to tell because we enter hell physically, bodily. In order to tell the story it’s important to start from the beginning. And talking about the most important sentiment: love, sex, passion. Dante is very carnal. He is not a priest; he is a man. Nobody during the middle ages could write such verses, talking about bodies, describing when they make love. He is telling us about lust. And about women. The first name in hell is the very ancient empress Semiramide. And the first monologue is done by Francesca, who is another woman. Paolo and Francesca, they are together, embracing, but Francesca is talking and Paolo is there crying. It’s the opposite of what happens normally: man they are talking and female they are crying. Dante was very modern. And he wrote the poem in order to see again the girl he loved so much, Beatrice. And the last canto is about the woman for excellence, which is the Virgin Mary. So it’s a female poem.

And the fifth canto is the first circle of hell. So it’s very good to tell because we enter hell physically, bodily. In order to tell the story it’s important to start from the beginning. And talking about the most important sentiment: love, sex, passion. Dante is very carnal. He is not a priest; he is a man. Nobody during the middle ages could write such verses, talking about bodies, describing when they make love. He is telling us about lust. And about women. The first name in hell is the very ancient empress Semiramide. And the first monologue is done by Francesca, who is another woman. Paolo and Francesca, they are together, embracing, but Francesca is talking and Paolo is there crying. It’s the opposite of what happens normally: man they are talking and female they are crying. Dante was very modern. And he wrote the poem in order to see again the girl he loved so much, Beatrice. And the last canto is about the woman for excellence, which is the Virgin Mary. So it’s a female poem.

And I chose the fifth canto because it’s beautiful. But every single canto is beautiful. The music, it’s not like Milton, or some poets [in whose works] the tune and the music is always the same for every character. Dante changes the music. To hear different styles of the rhythm and the music, it’s like to hear Beethoven and Duke Ellington together, or Bach and Jimi Hendrix playing together. It’s exactly like this.

You’ve been doing these readings for three years now. Do you want to continue? Is this what you want your main focus to be?

I would like to stop, but I am not able to stop. Because they ask for this show around the world — in Japan, in Korea, in South America. It’s incredible. Just for Dante Alighieri. I think I will continue in Italy because I left behind some towns in previous shows. So I go now to Verona. They ask for two more shows, that I did already three years ago, with 24,000 people. So have to I repeat. But then I have to stop. Because I would like to make not a divine comedy but a comedy — a movie. I would like to do a comedy very strongly. But I don’t have any idea because I am so completely so immersed in Dante, in the abyss of God.

After “Life Is Beautiful,” was it difficult to go back to making funny movies? Did that feel like a step back?

Of course my life changed a lot after “Life Is Beautiful.” It also changed the reception from other people to me. When I met somebody after “Life Is Beautiful” they treat me like a maestro. Before it was [big voice] “Hey, Benigni!” Then it was [little voice] “Oh, Mr. Benigni, how are you ...” They changed. [Laughs.]

Four years ago I was taking lessons for piano. That I liked. But I stopped because the man I called to have a lesson with, he called me maestro. [Laughs.] Said, “Maestro, put the hand here ...” No, maestro, you are the maestro! It was exactly after “Life Is Beautiful,” and I understood something was changing. [Big voice] “Hey maestro! Do re mi!” [Little voice] “Maestro, this is do ...”

Has that made things difficult in your career? How can you top it?

Ah, but this is good. This happens once in a life. I don’t want to repeat this moment. I just continue to make what I love. And the Divine Comedy I love very much. What I did before was comedies. This is the normality.

So you don’t want to do more serious roles. You want to do comedy.

In my life, everything I did, inside there was always something, you can call it profound, but this is not the right world. Something that goes that in the way of moving a little. Also in “The Little Devil,” or “Johnny Stecchino,” or “The Monster” — there was a vein of ...

Serious? Dark?

No serious, no dark. A little more profound. Something that goes inside, to touch for a moment. This has been my style. But in the beginning it was 90 percent comedy and 10 percent [the other side]. Now it is a little more 50-50. It’s my style. But we are going to find our style during our lives. So I start with this little part of more deep, then I go more 50-50 if can call deep what I’m doing. Something that can move. I feel this. I feel very sincere. Because I like it, when I go through Dante, through this immersion in this abyss, really, of God. I like to talk about this, and I can allow myself because I am a comedian. Only comedians can talk about death, life, God and Virgin Mary. If I was a tragic actor, I couldn’t allow myself. But with this accent I can do it. I can talk with death in person because I am a clown. Yes. And I am proud to be a clown — very much.

Italians know that you have another side to you. But I don’t know if Americans do.

In Italy they know that I am a real clown sometimes, but now they really are expecting from me something more profound. In the United States they know me only for “Life Is Beautiful,” which is a real tragedy. The style of “Life Is Beautiful” is not comedy. It is a comic body inside a real tragedy. Tragedy in two words is something that starts in a happy way and ends up in a very dark and sad way. And this is “Life Is Beautiful.” The Divine Comedy is called comedy because it’s the opposite: it starts in a very sad and terrible way and ends up with a happy ending. Happy because he is describing physically the face of God. And he telling us, “You are God.” He is describing your face, my face. Really this is shamelessness — incredible. [Laughs.]

How does it feel when you are doing the show?

I am full of emotion, of course. Because I am not able to find a way to be quiet there and to act in a professional way, like Laurence Olivier. I am always discombobulated. How do you say, when you are in a flurry, in tumult. Especially when you are physically in front of people. There is always something you cannot hold back, something you cannot manage. My feelings are ... great.

After “Life Is Beautiful” a lot of Americans expected that you would be making Hollywood movies. But the films you made were Italian, and they didn’t do very well over here.

Yeah, I know. Like my previous movies they didn’t do well here. Just “Life Is Beautiful.”

But I received a lot of offers, from the United States especially, also from France and from Spain, etc. Americans and Hollywood, they were very generous, especially giving me three Academy Awards. And I was sincere when I jumped on chairs. Because I tried to fly. For the surprise. I didn’t really expect my name to be told by Sophia Loren, screaming “Roberto!” And in order to demonstrate my gratitude, with all my exuberance I tried to fly, really to fly. Because this was like a big kiss, an embrace.

I received a lot of offers, sometimes to make a sequel of “Life Is Beautiful” or something related to the concentration camps, or during this period of history. Never in my life will I do this, never. And they offered me a lot of money. [Sleazy voice] “So, do a sequel ...” My God, you have to torture me, torture me. I received many, many subject ideas about this. Some were interesting. But I can’t, I can’t. Really, I can’t.

Or sometimes they offered me the cliché of Italians: the pizza man, the mafia man in a parody of the mafia, or fireworks with Italians in United States, with the south Italy family. But I am not south Italian. I like very much the south of Italy. But I am well known in Italy as Tuscan. And to find a character for a comedian is not that easy sometimes. We talked about a project with Jim Carrey, who I respect and like very much. Or Robin Williams.

I also received offers from many major companies to stay here in the United States, in Hollywood, to write with somebody. They give me a little house there to study, to write. But what can I do? My roots are in Italy. My life is there. I prefer to continue my life, to try to have a normal life, to do what I like. Maybe sometimes I have been wrong with some movies. Maybe “Pinocchio” didn’t receive the success I was expecting. Maybe something was wrong. Anyway, I try to do my best. I was sincere. I was honest. But I am sure this path that I took is the right path.

I still think of “Down by Law” ...

Ahh, it was beautiful.

... as a definitive moment in your career, as the Italian guy in America who doesn’t really fit, but you do your thing anyway.

Thank you. You’re right. This was another magic moment. Not easy to repeat. It happened one time, with Jim Jarmusch. He is a kind of director who is so respectful for foreign cultures, and he is a very cultivated man. My friendship with him is very close still. Once a week we call each other.

I talked to him the other day, and he said that over the years he has written a number of things with you in mind, but none of them happened. Why not?

I was busy with something, he was busy. But we did “Night on Earth.” It was tentative with another. I think we will do something again. There is a great feeling between me and him. But to repeat this character Roberto from “Down by Law” ...

About Dante: You said you view yourself as primarily an entertainer, not a professor. But clearly you know this subject very, very well. What sort of research or preparation do you do to talk about this for two hours?

My God. First of all, when you like something it’s easer. I really like Dante, so I read everything I find about him. I read a lot of commentaries, notes. And I also read aloud. Because it explodes the cosmos of illumination when you recite aloud. And I study the way to recite the canto at the end, because I am an actor above all. I am not a Dantist. When I do the commentary I try to be right, the way that I like. Because commentaries about Dante, there are billions. It is not enough, an entire life, just to read commentaries about one canto. There are really buildings of books about Dante.

I try to recite in a way that nobody did before: very simple, putting me behind Dante, not in front of him. Actors, normally when they recite Dante, they put themselves before him. Me, I am back, low-profile.

Is that difficult? I can’t imagine you being low-profile.

No, no. Because in this case, with the low profile you explode. You explode. You present the beauty, so you are part of this beauty. Otherwise you are a shadow of Dante. Putting me in the shadow of Dante, I become illuminated. It’s like a candle trying to illuminate the sun.

[Here Benigni discusses some technical, phonetic details of his performance, including how he pays close attention to individual syllables and the accents of each line, and particular aspects of Tuscan pronunciation.]

You know, in the United States there are the greatest Dantists in the world, more than in Italy. It’s incredible. Each year there are 20 translations of Dante in English, and 15 are from the United States. Last week I received a translation from Korea, from a professor. No joking. I can show it to you. If you see my room in Rome, I have a room only with translations of the Divine Comedy from around the world. “Try to read this, why don’t you come...” The latest is in Korean, and also in vernacular. Because Dante wrote not in Latin but in the vernacular language. You use the Hollander translation. Why do you use that one?

You use the Hollander translation. Why do you use that one?

In the United States there is Pinsky, Mandelbaum. My God, you have really great translations, maintaining the triplets, or blank verse. But Hollander my favorite because he not trying to write a book in his notes. Many, many commentators, they write another book with their notes. The most serious, mature way to look at Dante at this moment, in my opinion, is Robert and Jean Hollander. I did for Robert Hollander — he translated “Paradiso” — I did an introduction for him.‡ My introduction was very funny, it was not serious. It was a letter to Dante, asking if he received the rights — money. Because everybody now is talking about him, and maybe he’s not receiving money. His money goes to the society of rights, and I don’t know how they use this amount of money. And poor Dante, he’s now in Purgatory ...

Really?

Yes. He put himself in Purgatory, with the superbos [i.e. the prideful]. “I am the best.” He put himself there. He is really a superbo. He knew that he was the greatest poet. So he knew his position was amongst the pride.

Anything in particular that you’re hoping to teach Americans about Dante?

I am not here to teach. I’m here to make a show. There is a difference. What I am repeating is the Divine Comedy is beautiful. This is my end. We can live without reading the Divine Comedy. We can live also without seeing the ocean, but it is better if you see it once. My God, you see only lakes. You say, “My God, the ocean.”

I am full of emotion to be in the United States. Because there are some cantos in hell where he is describing Los Angeles when you are landing, or New York.

What parts remind you of New York?

Oh, la bolgia ottava, the 26th canto — full of little lights when he is landing, looking from a skyscraper like this, looking at the bolgia — infinite lights, traffic, people. The fraud. Describing like a landing in New York or in Los Angeles. We can think that Dante flew in the Middle Ages, because he is describing a landing. [Getting up from his seat, growing more animated.] And the 26th is also when Ulysses goes in the mountain in Purgatory, and it is set in the United States 200 years before Columbus. Because he is describing the journey of Ulysses with his friends in the ship. They go and the direction is Spain: left, south-left, south-left. And describing the moon and the other part of the planet, the equator. They go exactly there. It’s San Salvador — about Florida. In Florida before Miami, there is the mountain of Purgatory. He has described the new world there. If you read it, it’s unbelievable. So it’s related very much to the United States.

In the 26th canto, Dante describes the lights like fireflies, like a farmer who sees billions of fireflies. And every single firefly is hiding a fraud — people like Madoff. Very cunning, very shrewd. These people are hiding inside the flame because they are hiding in life. The Florentines, you know, they invented finances. The fiorino — in the Middle Ages it was like now the dollar, for the change ...

Banca ...

Banca, exactly. Banca rotta is from Italian: bankrupt. Rotta means break. It’s a single word, invented during this period, from Florence. When they couldn’t pay they came and they broke the banks: banca rotta, broken bank. When you go to the bank now and they destroyed everything, this is bankrupt: rotta la banca. So finanza is a Florentine name. The first time people started to make money back from money, from nothing, that now we are ruined for this. Change, cambio, credito, casso — it started during Dante.

Caro Ben — I thank you very much.

* He may be exaggerating here. According to my Italian sources, his first reading, in November 2007, had about 10 million viewers, a 36 percent share. Others, which aired late at night, averaged 2.2 million. That may not be 50 million (the entire population of Italy is only 60 million), but it’s still huge.

† “L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle” (“Paradiso” XXXIII.145), the last line of the Divine Comedy.

‡ Actually, according to Hollander, it was for a special Italian edition of “Inferno.”

Ancient history: Thurston Moore, Al Green, Lou Reed, M.I.A., Stew.

No comments:

Post a Comment