“Songs drive along the same neural pathways that dreams do. So using them — misusing them — to sell hairspray, it just seems obscene.”

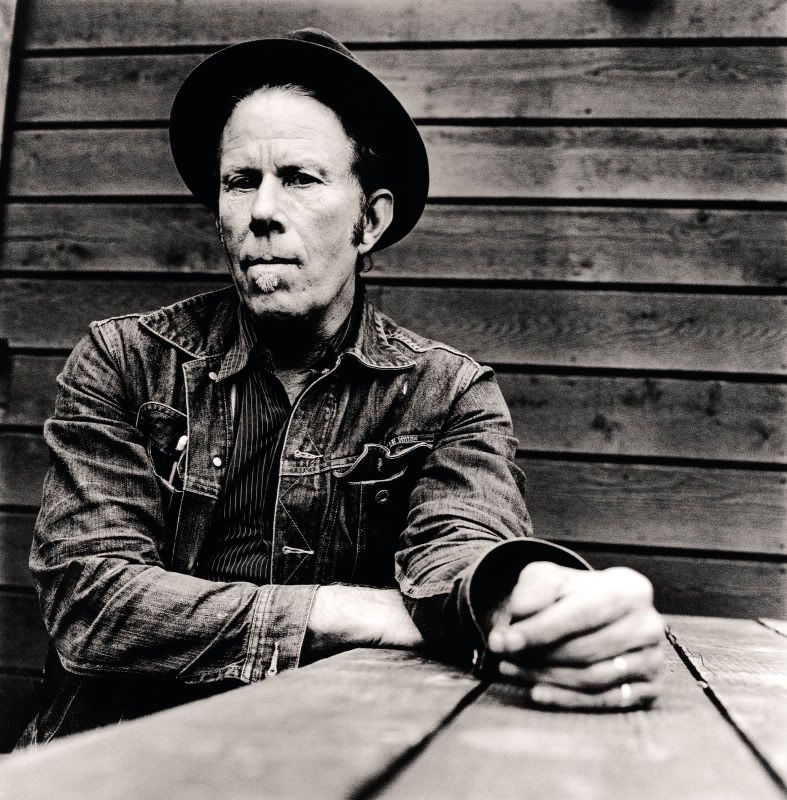

In 1988 Tom Waits sued Frito-Lay for using a sound-alike in a Doritos commercial, and won $2.5 million in damages. That case, and a similar one by Bette Midler, became landmarks in establishing an artist’s right to his or her voice. But Madison Avenue was undeterred, and for the next two decades Waits would fight many advertisers who copied his distinctive vocal style without permission.*

It happened again in 2005, when Audi and Opel used suspiciously similar-sounding singers for European ads. Waits sued both companies. I wrote a news item, and got a quote from Opel saying they had never considered Waits for the ad — despite a paper trail clearly showing that they had approached him and been turned down flat.

Waits was apparently so pleased with this that he agreed to an interview about it, something he doesn’t often do. I remember picking up the phone around 6 p.m. on Jan. 18, 2006, and hearing, “It’s Tom!” We talked for about 45 minutes, and although the resulting story turned out fine, it was frustrating how few of his marvelous quotes made it into the piece.

Here is a transcript of our conversation, minus a few trims for redundancy or irrelevance.

It must be extremely time-consuming and expensive to pursue these cases. Why is it so important to you to do this?

I ask myself that sometimes. Because there are things I would rather be doing. It does take a tremendous amount of time, energy and money. But in a way you’re building a road that other people will drive on. I have a moral right to my voice now. It’s like property. There’s a fence around it, in a way. In Spain now there’s such a thing as moral rights. So that’s a good thing.

In both these cases — the Scandinavian/German Opel thing and the Spain Audi deal — they called me first to ask me if I would do the commercial. Then, when I politely declined, they turned around and hired an impersonator. So they’re really left hanging out there in the wind legally, since I had documentation that they asked me; it only strengthened my case. But there’s plenty of other situations where they just out-and-out do it. There’s a whole sound-alike industry, and it has to eat too. Like flies at a picnic, you know. “Enjoy your lunch, but we live here too.”

Why do you think they want a voice like yours selling cars and salty crackers?

Maybe it’s because I don’t want it. They want me more. Or maybe over there they think that I’m just kind of a nobody. “I found this really weird guy in my record collection. I think he’d be good for the Harley Davidson account or something.” I don’t know.

Does it happen a lot, given that the Frito-Lay case is such a well-known precedent?

It does. I get people that usually call me, say, “Hey, I saw this ad. Sounds just like you. I didn’t think you did ads.” I don’t!

Why not?

It’s part of an artist’s odyssey, discovering your own voice and struggling to find the combination of qualities that make you unique, whether you’re Yma Sumac, or Walter Brennan, or Caruso, or William Burroughs, or Sister Rosetta Tharpe — you shape yourself. It’s kind of like your face. You’ve got an identity. It’s like a fingerprint. So now I’ve got these unscrupulous doppelgängers out there. [Laughs.] My evil twin who is undermining every move I make. That’s the way it feels.

You’re as defined by the things you say yes to as the things you say no to, right? So if you saw Ralph Nader lying in his underwear stroking a panther on a billboard, would that impact his position in the public’s mind on global warming? Hell, it would change whole definition of global warming! [I laugh.]

Does it offend you more that somebody is copying you, or that they’re doing it to sell a product?

I don’t mind if someone wants to try to sound like me to do a show. I get a kick out that. They got these bands over there in Europe that do my songs, have a singer with a really deep voice. It’s my own little raggedy version of Beatlemania. [Laughs.] These little bar bands that try to sound like me.

But the product stuff, it bugs the hell out of me. The idea is to make it so commonplace that you barely notice that the whole world is being dominated and controlled by big business. I didn’t get into this to write jingles. I’m trying to have some effect on the culture, and my own growth and development.

I make a distinction between people who are using voice as a creative item and people who are selling cigarettes and underwear. It’s a big difference. We all know the difference, and it’s stealing. They get a lot of out standing next to me and I just get big legal bills. It’s like someone coming into your house and stealing something. It slowly erodes my own credibility. So that’s a pain.

Most of these companies operate more like countries than companies. They’re so large. And the way they behave is kind of like the might and the right of a country, the way they roll over you. They don’t think anything of taking something that they want, because they’re going to get a parking ticket. And it doesn’t even ever reach the brain of the company. The news of this is just like gum on the bottom of their shoe.

When it comes to the face that most of them want to put on for the public, they don’t want to wear corporate feathers. They masquerade more like one of us. So that’s why want to wear your music. It’s the first thing that gets your attention: “Hey, I know that song.” Now they’ve got ya — that’s the foot in the door.

You said that you’re “building a road.” Do you get support from other musicians?

To be honest with you, I think it’s gotten rather flea-bitten. But there are several people that are scrupulous, and they really stand next to me. Neil Young’s against it, Springsteen’s against it, people like that. Those guys are big guys.

But for the most part I think the idea is that ultimately the only way you will be able to get exposure is by tying yourself to a new car. Out on the hood. I think it’s getting like that now. You try to make a voice, and get heard, but it’s getting to the point where — like these blue-jean ads, and all that. Nobody thinks anything of it, for the most part. They think, “Oh, I saw you in a magazine, man, that was cool. How you doin’?”

Do you feel that you’re part of a dying breed?

I’m not dying, and I’m still breeding. I only know how it is for me. I can’t really legislate my own morality about it. I know how I feel about it, and it just doesn’t go down right for me.

You’ve done well financially with these cases, right?

It barely comes close to scratching the surface of your legal bills. I think with the Spain thing it was 70,000 euros, or something like that. That’s like a couple of days with a lawyer over there. Plus you’re hiring people 5,000 miles away. You have to stay on top of it. It’s a pain. It’s like making dinner at the bottom of a swimming pool.

Do the lawsuits interfere in making music?

Oh, yeah. You gotta get on the phone at 4 in the morning with guys who don’t speak English. It’s no fun. I have a certain amount of zeal about it, and my wife has got a really great mind for this. She’s always been in my corner. We kind of slug it out together, like a tag team.

Can you quantify how much of an investment it has been for you to pursue these cases?

Oh, Jesus. I don’t really know. Millions! No, not millions. But I’ve had a lot of them. Some of them settle. You go, “OK, you gotta put an apology in the paper.” In Italy, man, it’s really crazy over there. They’ll just take a record of yours and they’ll put a new cover on it and they’ll glue it to the front page of their daily paper. And they’ll say, “Get the paper, and for an extra 50 cents you get this Tom Waits record.” Stuff like that. They just do it. And you just go, “What?!” Is the record selling the newspaper, or is the newspaper selling the record? Which is it?

How many of these suits do you have going on now?

This one [in Spain] just wound up with a decision. This other one in Germany, Opel — they asked me to take the Brahms Lullaby, sing the melody of it, add some kind of phony words. I said no. So they did a car commercial, putting a car to bed in the ad, and they hired a guy that sounds just like me doing it. So we attacked them. [Laughs.]

Whatever you do to create something unique in your voice, it’s a spell that you’re able to weave with it. The ads kind of lay eggs in your brain. They’re getting more and more expensive. They get really insidious. And then there’s more and more people that you don’t think would ever do them, doing them. You can’t believe it. It’s like, “Why are you doing that? You don’t need money.”

You think the Who needs money? They got to do car ads? So why do they do it? Because I think they think they feel current or something, just to be around. I guess they’re not getting any airplay.

For a lot of younger musicians, advertising isn’t really about imitation, since their voices aren’t as well known. So for them to get some money to have their song in a car commercial, might that be a good thing?

I don’t know. And I think that’s the trouble. There used to be a very clear answer to that, and now people are going, “Maybe this could be a good thing for me.”

Could it be?

Maybe for them, but not for me. You build up a certain amount of good will with your audience. And I think I’ve taken the road less traveled and all that. For a band to get a break doing an ad for a car — Why don’t you go get a gig at a club? Do it the old-fashioned way.

I do believe in my feelings about it and why I think it’s a bad thing. It was a bad thing for me because songs are deeply meaningful to me. They drive along the same neural pathways that dreams do. So in a sense, using them — misusing them — to sell hairspray, it just seems obscene to me. It weakens the muscles of the song. It pisses me off.

I think other artists doing commercials erodes everyone’s credibility. It gets to a point where songs really are like jingles — they contain jingle material, and they’re bouncy, and surface, and simpleton. And it’s more about how they’re marketed and the size of the campaign than that which you are marketing. These songs that they’re putting in these ads aren’t nothing, if they’re willing to pay $5 million for usage. They know the great power that a song carries.

Everybody’s got a different way of seeing it, and that’s just mine. John Densmore’s got some really great thoughts on the topic.

Are you offered that kind of money?

I’ve been offered a million bucks for a beer commercial, restaurants and stuff like that. I’m not a big-hit, iconic artist. I think they maybe like me more because I’m more obscure, and I seem more beat and more inside, you know, wink-wink. Maybe that’s why I get hit.

What’s the state of the Opel case in Germany?**

It’s just grinding through the snail pace of the court process. You throw a rock and you wait two years to hear it go through a window. I do other things in the meantime. [Laughs.] It’s not like my life is built around it. But it is a pause. My life is now like a pause in between lawsuits.

I must get a kick on a certain level, the David and Goliath approach. The old guy with the shotgun on the front porch. I’m the old guy now.

But do you think it might deter some of it?

Maybe. “Waits didn’t do it, we’re not doing it. Fuck you, man, I quit!” So who knows. You don’t always know when you stand up, who’s standing near you.

As far as changing the way these companies do business, it’s a beginning. They really hate apologizing and really hate bad publicity. They’re not going to change anything until punishment costs more to them. If you can’t get Bob Seger to do something for a million bucks, get an impersonator to do it for 30 grand. That’s kind of what they did with me. I’m not even for sale. They still ask you and they tempt you, wave something in front of your face. They figure everybody has their price. It’s not that I can’t be bought because I haven’t been offered enough money. For a lot of people that’s the case.

I want to be kryptonite. These aren’t the people that are my heroes, big corporations and ad agencies. I’m a musician. That’s my world. I’m just saying, “Find another way.” But yeah, maybe I’ll have some influence on younger people. It becomes part of your profile. And what you say you’ll do and what you say you won’t do becomes part of your music, too. Do you want to see a guy do a concert who’s on-air every five minutes doing ads for cars ad stuff? It kind of mixes his message. I got to try to keep my work as clean as I can.

The other thing is that they aren’t just your songs. Because once people hear them then they think, “That’s my song.” They say, “Look what they done to my song, maw! Look what they done to my song.” So there’s that angle too. That’s what Densmore was saying about all the Doors songs. It’s like the soundtrack to the Vietnam War, and now you want to turn them into jingles? No way, man. You got to know what you believe in. Stand for something or fall for everything, right?

I probably sound like ... I don’t know, maybe I’ll run for office.

Good. We need people with some principles.

No, I’m just kidding.

* Waits isn’t totally without stain here. In 1981 he recorded a voice-over for a commercial for Butcher’s Blend, a dog food made by Purina. Here it is:

I hadn’t known about this when I conducted the interview. If I had, I would have asked him about it.

** He won a year later, via settlement.

Golden oldies: Roberto Benigni, Thurston Moore, Al Green, Lou Reed, M.I.A.

1 comment:

Butcher's Blend just has that little something extra that deems it worthy of Tom lending his talents. Nice work!

Post a Comment