I may be a sucker for all this early Watchmen hype, but I don’t care.

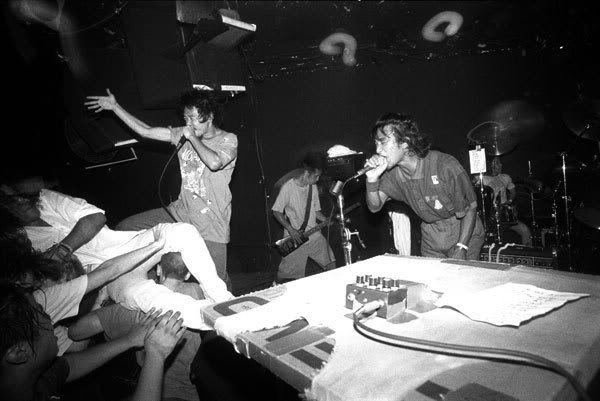

The Boredom Festival has an impressive reconstruction of “Tales of the Black Freighter,” the grisly comic-within-a-comic in Watchmen. It’s an excellent example of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s multilayered storytelling style, and it’s a great story to boot. In it, “Black Freighter” panels alternate with scenes of New York in 1985, where a boy reads the vintage-E.C.-style pirate book at a newsstand. (On the corner of 40th and Seventh — lemme hear it for my nerds.) Reflecting multiple threads of the larger “Watchmen” narrative and foreshadowing the bloody climax, it’s also a tribute to the comic form itself.

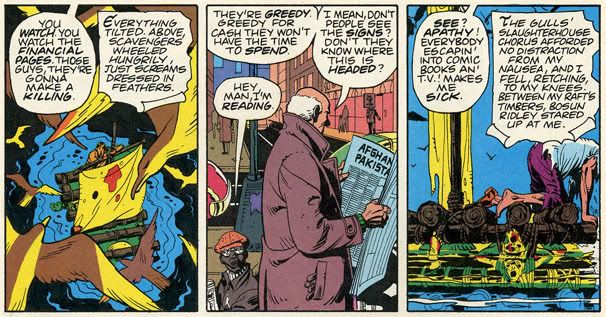

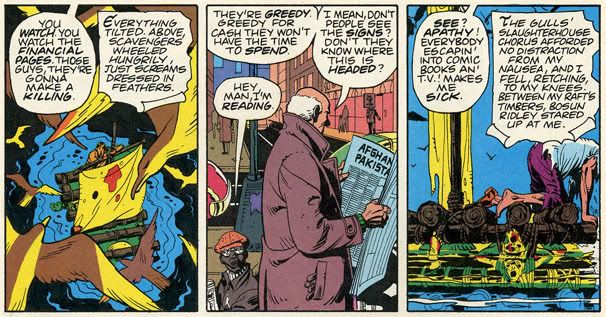

Here’s what it looks like. The round word balloons are for “real life,” the scrolled text for “Black Freighter”:

Evidently with some time on his hands, the Boredom blogger isolated the pirate story by scanning every page on which its panels appear and eliminating all non-“Black Freighter” art and text, then consolidating the panels to form one continuous 20-page book. (In the original, the “Black Freighter” story is interspersed between Chapters 3 and 11.) The resulting pages look like this:

The pirate story isn’t hard to follow in the original, but this brings it to the forefront and removes all possibility of distraction. The plot is brutally concise: Shipwrecked castaway races phantom pirate ship home, riding a raft made from corpses (and fending off sharks along the way); ashore, thinks pirates arrived first and goes on mad killing spree to reach family; realizing mistake, accepts his damnation.

The clever thing is that pirate stories were never a major part of comics’ Golden Age. Superheroes, horror and sci-fi were the dominant genres, at least in the action/young-male category. (Romance titles were also huge, but never developed the same tradition or literary weight.) As explained at the end of Chapter 5 in a fictitious comics history, Moore and Gibbons’s idea was that kids in this alternate 1985 would not have been interested in masked vigilantes because those characters were already a part of real life, and in fact were sanctioned by the government. Rather, young readers preferred the world of pirates, a moral vacuum of criminality and murder in which authority figures were largely absent.

Gruesome fatalism sets the tone for the late-Cold War society depicted in Watchmen. The black pirate sails match the black-on-yellow triangles of the ubiquitous fallout shelter signs, and in both cases there’s no hope of survival. The fallout shelters, of course, offer no real sanctuary from war: people are going to die when the bombs drop, just as the poor schmuck in “Black Freighter” has no way out once the black sails arrive. And the one-man-against-the-world theme satisfies a desire to both escape from civilization and dominate it — like Adrian Veidt in his fortress in Antarctica, and Dr. Manhattan in his on Mars.

Last month David Hajdu, who has written books about Billy Strayhorn and the Dylan-Baez-Fariña-Fariña folk/love/BS quadrangle, published The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, about the public crackdown on comics in the 1950s. I haven’t read it yet, but it’s been getting good reviews, and I’ve always considered this an important topic that has never been sufficiently explored. The comics scare was a low-culture reflection of the witch-hunts that were already claiming intellectuals and entertainment figures, with dubious experts like the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham testifying in Congress about how violent comics were corrupting our youth. Among his many absurd and inflammatory quotes: “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry.”

“Black Freighter” is a 100-proof distillation of what so frightened Dr. Wertham. Besides its graphic violence, besides its themes of slaughtered innocents and last survivors bound for hell, the language itself is merciless, with gross and appropriately turgid lines like: “I’d swallowed too much birdflesh. I’d swallowed too much horror.” That’s both a homage to the gore and melodrama of E.C. and an illustration of how cruel the Watchmen society had become. Horror comics, and life in general, just kept getting more dreadful, increasingly focused on war and extinction. Even the salvation Veidt seeks is still mass murder.

In Chapter 5’s fake history, it’s explained that the government stepped in during the ’50s crackdown and protected comic book publishers, since superhero-like figures were on the federal payroll:

With the government of the day coming down squarely on the side of the comic books in an effort to protect the image of certain comic book-inspired agents in their employ, it was as if the comic industry had suddenly been given the blessing of Uncle Sam himself — or at least J. Edgar Hoover.

So comics never got censored or homogenized, never forced underground. And the publishers — who in the real 1950s were selling 80 to 100 million books a week — never lost their grip on youth culture. In fact they might have made things worse for the society at large, by becoming a de facto propaganda machine: the destruction that Dr. Manhattan and the Comedian wrought on Vietnam and elsewhere could be justified — and Nixon could elected for four terms — precisely because all-American comic book heroes were involved.

This is the genius of Watchmen. More than any other book — especially during the 1980s, the heyday of literary comics — it drew vivid and frighteningly plausible connections between reality and fantasy, and used the mythology of comics to explain the psychology and politics of its time. (Remember, this was still very much the era of Russkies, the Berlin Wall and Chernobyl.) That’s the highest achievement any book of any kind can hope for.

The movie will suck. That’s pretty much a given. (The director, Zack Snyder, has already said he’s going to soften the ending. Need another reason? “Tales of the Black Freighter” will not be part of the movie, though it will be on the DVD release — hey, it’s not an important part of the story, after all, just a carrot to entice retail sales.) But any opportunity to revisit the book is welcome. It’s more brilliant every time I read it.

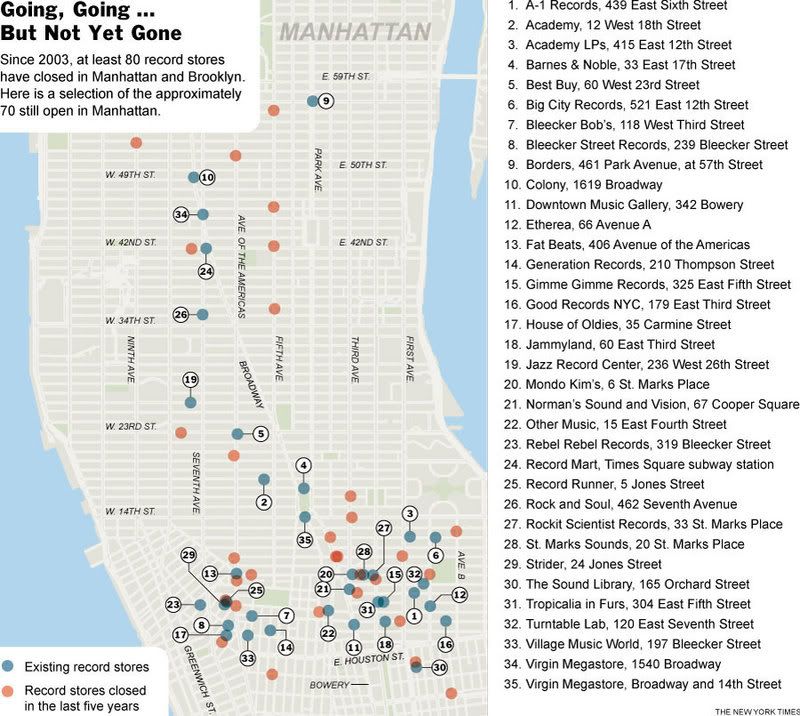

The map could legibly cover only from 59th Street to Delancey Street. That left out J&R World and a bunch of stores uptown, among them a number of important Latin outlets. We included one Best Buy, one Barnes & Noble and one Borders to have those chains accounted for, but otherwise didn’t include the big boxes — partly because, much to my irritation, I couldn’t confirm on deadline exactly which carried CDs and which didn’t.

The map could legibly cover only from 59th Street to Delancey Street. That left out J&R World and a bunch of stores uptown, among them a number of important Latin outlets. We included one Best Buy, one Barnes & Noble and one Borders to have those chains accounted for, but otherwise didn’t include the big boxes — partly because, much to my irritation, I couldn’t confirm on deadline exactly which carried CDs and which didn’t.